Acute bronchitis

| Acute bronchitis | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

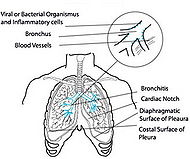

This image shows the consequences of acute bronchitis. |

|

| ICD-10 | J20.-J21. |

| ICD-9 | 466 |

| MeSH | D001991 |

Acute bronchitis is an inflammation of the large bronchi (medium-sized airways) in the lungs that is usually caused by viruses or bacteria and may last several days or weeks.[1] Characteristic symptoms include cough, sputum (phlegm) production, and shortness of breath and wheezing related to the obstruction of the inflamed airways. Diagnosis is by clinical examination and sometimes microbiological examination of the phlegm. Treatment for acute bronchitis is typically symptomatic. As viruses cause most cases of acute bronchitis, antibiotics should not be used unless microscopic examination of Gram stained sputum reveals large numbers of bacteria.

Contents |

Cause/etiology

Acute bronchitis can be caused by contagious pathogens. In about half of instances of acute bronchitis a bacterial or viral pathogen is identified. Typical viruses include respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, influenza, and others.

- Damage caused by irritation of the airways leads to inflammation and leads to neutrophils infiltrating the lung tissue.

- Mucosal hypersecretion is promoted by a substance released by neutrophils.

- Further obstruction to the airways is caused by more goblet cells in the small airways. This is typical of chronic bronchitis.

- Although infection is not the reason or cause of chronic bronchitis it is seen to aid in sustaining the bronchitis.

Signs and symptoms

Bronchitis may be indicated by an expectorating cough, shortness of breath (dyspnea) and wheezing. Occasionally chest pains, fever, and fatigue or malaise may also occur. Additionally, bronchitis caused by Adenoviridae may cause systemic and gastrointestinal symptoms as well. However the coughs due to bronchitis can continue for up to three weeks or more even after all other symptoms have subsided.

Diagnosis

A physical examination will often reveal decreased intensity of breath sounds, wheezing, rhonchi and prolonged expiration. Most doctors rely on the presence of a persistent dry or wet cough as evidence of bronchitis.

A variety of tests may be performed in patients presenting with cough and shortness of breath:

- A chest X-ray that reveals hyperinflation; collapse and consolidation of lung areas would support a diagnosis of pneumonia. Some conditions that predispose to bronchitis may be indicated by chest radiography.

- A sputum sample showing neutrophil granulocytes (inflammatory white blood cells) and culture showing that has pathogenic microorganisms such as Streptococcus spp.

- A blood test would indicate inflammation (as indicated by a raised white blood cell count and elevated C-reactive protein).

Treatment

Antibiotics

Only about 5-10% of bronchitis cases are caused by a bacterial infection. Most cases of bronchitis are caused by a viral infection and are "self-limited" and resolve themselves in a few weeks. Acute bronchitis should not be treated with antibiotics unless microscopic examination of the sputum reveals large numbers of bacteria. Treating non-bacterial illnesses with antibiotics leads to the promotion of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which increase morbidity and mortality.[2]

Smoking cessation

Many physicians recommend that to help the bronchial tree heal faster and not make bronchitis worse, smokers should quit smoking completely to allow their lungs to recover from the layer of tar that builds up over time.

Antihistamines

Using over-the-counter antihistamines may be harmful in the self-treatment of bronchitis.

An effect of antihistamines is to thicken mucus secretions. Expelling infected mucus via coughing can be beneficial in recovering from bronchitis. Expulsion of the mucus may be hindered if it is thickened. Antihistamines can help bacteria to persist and multiply in the lungs by increasing its residence time in a warm, moist environment of thickened mucus.

Using antihistamines along with an expectorant cough syrup may be doubly harmful encouraging the production of mucus and then thickening that which is produced. Using an expectorant cough syrup alone might be useful in flushing bacteria from the lungs. Using an antihistamine along with it works against the intention of using the expectorant.

Prognosis

Acute bronchitis usually lasts a few days or weeks.[3] It may accompany or closely follow a cold or the flu, or may occur on its own. Bronchitis usually begins with a dry cough, including waking the sufferer at night. After a few days it progresses to a wetter or productive cough, which may be accompanied by fever, fatigue, and headache. The fever, fatigue, and malaise may last only a few days; but the wet cough may last up to several weeks.

Should the cough last longer than a month, some doctors may issue a referral to an otorhinolaryngologist (ear, nose and throat doctor) to see if a condition other than bronchitis is causing the irritation. It is possible that having irritated bronchial tubes for as long as a few months may inspire asthmatic conditions in some patients.

In addition, if one starts coughing mucus tinged with blood, one should see a doctor. In rare cases, doctors may conduct tests to see if the cause is a serious condition such as tuberculosis or lung cancer.

Prevention

In 1985, University of Newcastle, Australia Professor Robert Clancy developed an oral vaccine for acute bronchitis. This vaccine was commercialised four years later.[4]

See also

- Chronic bronchitis

References

- ↑ Wenzel RP, Fowler AA (2006). "Clinical practice. Acute bronchitis". N. Engl. J. Med. 355 (20): 2125–30. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp061493. PMID 17108344.

- ↑ Hueston WJ (March 1997). "Antibiotics: neither cost effective nor 'cough' effective". The Journal of Family Practice 44 (3): 261–5. PMID 9071245.

- ↑ Bronchitis, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 2007-04-20, http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/bronchitis/DS00031/DSECTION=1, retrieved 2008-05-30

- ↑ Clancy RL, Cripps AW, Gebski V (Apr 1990). "Protection against recurrent acute bronchitis after oral immunization with killed Haemophilus influenzae". Med J Aust. 152 (8): 413–6. PMID 2184330.

External links

- Acute Bronchitis FamilyDoctor.org (American Academy of Family Physicians)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||